When did the history of hacking begin? If you’re guessing the second half of the 20th century, you have to go a little further upstream. It wasn’t even breaking Enigma-encrypted messages during World War II.

We are more than 180 years away from the first known hack of a communications network (spoiler: it wasn’t a phone call, Alexander Graham Bell didn’t make his first call until 42 years later).

Chappe’s Telegraph

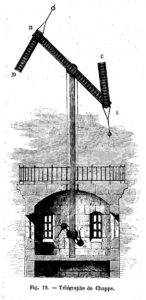

In 1794, French inventor Claude Chappe came up with a system of visual semaphore telegraphs. By adjusting flexible arms placed on a tower (mast), it was possible to display letters, numbers and some special characters, such as the beginning and end of a communication or the deletion of the last character in case of a typo. In this case, rather “misbending”.

In 1794, French inventor Claude Chappe came up with a system of visual semaphore telegraphs. By adjusting flexible arms placed on a tower (mast), it was possible to display letters, numbers and some special characters, such as the beginning and end of a communication or the deletion of the last character in case of a typo. In this case, rather “misbending”.

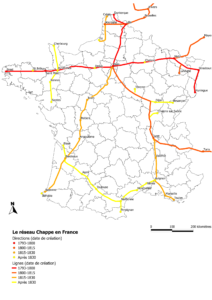

The individual towers were spaced apart so that one could be seen from one to the next. Thus, the message could spread from one tower to the next until it reached its destination. It is reported that the speed of the message was up to 500 km per hour.

In France, a network of Chappe visual telegraphs was built during the 19th century to serve the needs of the state (and especially the army). For example, there were 58 stations on the route between Paris and Brest. But ordinary citizens could not use the services of this communication network.

The communications even used end-to-end encryption. Since military secrets were being transmitted via the telegraph network, it was not very appropriate for anyone with a view of the telegraph tower to be able to read the communications. Thus, the sender and receiver had an agreed key with which to encrypt their messages. The tower operators along the way just repeated the encrypted message character by character without being able to decipher what the contents of the message were. The sender and recipient of the message thus had more privacy in 1800 than Facebook Messenger users in 2021 (more on messenger encryption here).

The communications even used end-to-end encryption. Since military secrets were being transmitted via the telegraph network, it was not very appropriate for anyone with a view of the telegraph tower to be able to read the communications. Thus, the sender and receiver had an agreed key with which to encrypt their messages. The tower operators along the way just repeated the encrypted message character by character without being able to decipher what the contents of the message were. The sender and recipient of the message thus had more privacy in 1800 than Facebook Messenger users in 2021 (more on messenger encryption here).

François and Louis Blanc

The Blanc brothers traded government bonds on the Bordeaux stock exchange. In such trading, speed of information is crucial – whoever has faster news from a central point of action (in this case Paris) has an advantage over other traders because they can better anticipate stock market movements.

Traditionally, news from Paris to Bordeaux was sent by stagecoach, which took five days. Some merchants tried to shorten this time by using carrier pigeons or hiring messengers. This was faster, but not significantly so. It was certainly not enough for the Blanc brothers. They knew there was a much faster way to communicate over long distances. But it was reserved for the army, and merchants could not use it. So most merchants continued to think about improving the aerodynamics of the pigeon. But the Blanc brothers were hackers (though they didn’t claim to be on Twitter, according to available sources). So they didn’t give up on the idea of using Chappe’s telegraph network.

Traditionally, news from Paris to Bordeaux was sent by stagecoach, which took five days. Some merchants tried to shorten this time by using carrier pigeons or hiring messengers. This was faster, but not significantly so. It was certainly not enough for the Blanc brothers. They knew there was a much faster way to communicate over long distances. But it was reserved for the army, and merchants could not use it. So most merchants continued to think about improving the aerodynamics of the pigeon. But the Blanc brothers were hackers (though they didn’t claim to be on Twitter, according to available sources). So they didn’t give up on the idea of using Chappe’s telegraph network.

The Plan

The telegraph operators were probably not the best-paid employees in France. So the solution might be good old-fashioned corruption.

The telegraph operators were probably not the best-paid employees in France. So the solution might be good old-fashioned corruption.

But if the Blanc brothers wanted to send messages in the standard way, they would have to bribe all the operators on their way from Paris to Bordeaux. Which could get expensive.

So they had to figure out how to solve this expensive inconvenience.

As mentioned above, the system included a symbol to erase the last character – the operator writes down the characters as he sees them on the semaphore and if he sees the erase symbol, he simply erases the last character and moves on.

This is what the hackers decided to take advantage of. They will send secret messages by following “their” character embedded in a regular army message with an erase character. Anyone who sees the semaphore can see this character, but the terminal tower operator will erase it from the paper (or not write it at all). Thus the message will be passed on while leaving no written evidence of it.

Socks as a data carrier

There was one more problem to solve. On the way from Paris to Bordeaux, there was still a tower in Tours (about 200 km from Paris) where messages were decoded and forwarded on without error. So the messages had to be sent from here. And they must have gotten to Tours somehow unobtrusively.

Fortunately, there was no need to send some extensive novels (that wouldn’t even be possible in this scenario), just a few arranged signals. And so parcels were sent to Tours from Paris containing clothes. The type of clothing (gloves, socks, ties) that was marked in the accompanying letter indicated whether a title was falling or rising in the stock market, and the color in turn the amount of change.

Hack

The hacking may have begun. An accomplice in Paris, according to the changes in the stock market, put the clothes in a package and sent it to Tours. There, the bribed telegraph operator (he received a one-off 1500 francs for his involvement in the conspiracy, then 150 francs every month, plus a bonus of 20 francs for each message transmitted) sent a message with “errors” inserted.

The hacking may have begun. An accomplice in Paris, according to the changes in the stock market, put the clothes in a package and sent it to Tours. There, the bribed telegraph operator (he received a one-off 1500 francs for his involvement in the conspiracy, then 150 francs every month, plus a bonus of 20 francs for each message transmitted) sent a message with “errors” inserted.

At the tower near Bordeaux, another accomplice waited with a telescope, watching the telegraph and writing down the characters that were marked as erroneous. And thus the messages reached our merchants, who were several days ahead of the others.

Disclosure

The system worked perfectly for two years. A total of 121 messages (and packages of clothes) were sent this way. Surprisingly, the sudden wealth of the telegraph operators (the normal daily wage of an operator was 1.50 francs) did not arouse suspicion.

The truth only came out when one of the operators fell ill and confided the whole matter to a friend before his death.

Surprisingly, the Blanc brothers suffered no consequences. French legislation simply did not prohibit the insertion of one’s own messages into the telegraph system. It didn’t occur to the legislators of the time.

And so they were later to become successful casino operators (including the Monte Carlo casino in Monaco).

As can be seen from the first documented hacking attack, the weakest link in security tends to be human.

Resources:

https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/T%C3%A9l%C3%A9graphe_Chappe

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fran%C3%A7ois_Blanc

https://www.schneier.com/blog/archives/2018/05/1834_the_first_.html

https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k4393846/f1.item